The summer of 1381 was a particularly tumultuous year in English history. Unlike many rebellions up to that point, the Peasants Revolt of 1381 was initiated by the lower classes. This revolt placed fear in the hearts of the English upper-class. Their ideas were progressive for their era, though their methods proved to be violent. I found this research to be fascinating and I noticed many common issues that we are still dealing with in today. These included handling the aftermath of a devastating pandemic, widening class divisions, out of touch government officials, taxation that does not represent the wants of the people, and an increase in the cost of living. The Peasants Revolt of 1381 was short but left a lasting legacy in history.

There are many factors that led to the Peasants Revolt in 1381. The Black Death swept into England in 1348 and caused a pandemic that eliminated nearly half of the population. This devastated the economy as a majority of the workforce had disappeared. Due to this labor scarcity, the lower classes found they had the advantage in the job market. They could demand higher wages and it was an employee market. With this newfound change in fortune, the lower classes could obtain more resources than ever before. A better station in life was finally an attainable goal. This was something that the upper classes disliked, as it was starting to encroach on the established hierarchy, as the feudal system was still alive and well.

In 1351 parliament passed the Statute of Laborers which prohibited higher wage requests or offering higher wages than what they were prior to the plague. The punishment for this would be large fines and imprisonment. Despite the increase in demand for workers and more opportunities available, this law ensured the laborers were still forced to remain destitute. It was obvious to the lower classes that these laws would destroy any chance they had of upward mobility, which naturally caused anger amongst the people.

The worst offence was the revival of the poll taxes. England had been fighting a war with France off and on (a conflict now known as the Hundred Years War). The burden of war had been constant for decades and was a large load upon the taxpayers. England was losing the war and there were no signs that it would improve. In 1377, 10-year-old Richard II inherited the throne after the death of his grandfather, Edward III. It would be difficult, as an average citizen, to have confidence that a child would be able to improve this situation.

The young Richard II inherited a tough situation militarily and economically. As a minor, he was reliant on those of his council which included his uncle, the unpopular John of Gaunt, and Simon of Sudbury, Archbishop of Canterbury. A poll tax was established which determined a standard amount of money to be taken from every man and woman above the age of fourteen, regardless of how much income one made. It served two purposes for the government: further funds for the war effort and it would prevent the lower classes from getting richer. Three poll taxes were passed within a four-year span and created more tension between the classes. People began to avoid paying these taxes, so the government appointed commissioners and tax collectors to enforce them.

The rebellions began primarily in the counties of Essex and Kent. The King began to send tax collectors to the villages to resolve the frequent tax evasion. In one instance, the villagers of Fobbing refused to pay. The tax collector, with the support of the military to enforce his demands, began to threaten the villagers. Yet, the people of Fobbing continued to hold strong and fought back against the soldiers attempting to arrest them. The mob drove out the soldiers with bows and arrows and the threat of violence. These were the first rebels to take arms and act and inspired others to act as well.

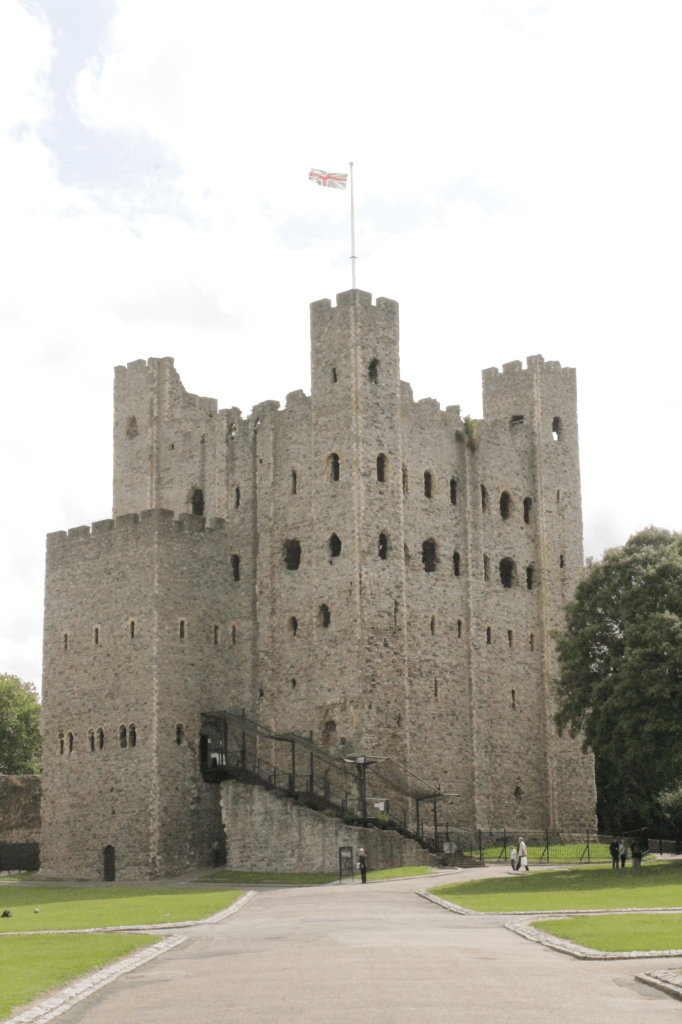

Details of what happened spread quickly throughout the villages and the common folk began to mobilize. In early June, Rochester Castle was taken by the rebels as they overwhelmed the guards stationed there. They plundered the castle and released prisoners. This showed that they had the strength and the numbers to have their revolt become a real threat.

Two leaders began to emerge from this chaos: Wat Tyler and John Ball. Wat Tyler was a craftsman from Essex and likely a former soldier who had been in battle on the continent. He proved to be a natural leader as the rebels began to make their way towards London. One of the prisoners released along the way included the radical priest, John Ball. Ball was very progressive for his time and had been arrested by the Archbishop of Canterbury for heresy. Ball preached against inequality, the corruption of the church, and tyranny. “When Adam delved and Even span, who then was the gentleman?” declared John Ball to the rebels in a sermon shortly after his release. He believed that there should be an end to lordship and church hierarchy in general. This was an extremely radical concept at that time but built the foundation for future revolts. In the Declaration of Independence, it is written, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” which echoes some of the sentiments Ball expressed.

Wat Tyler and John Ball brought together a common mission for the peasant rebels which united them into a strong force that continued the advance towards London. They wanted the opportunity to bring their grievances directly to the King (who they believed was ill advised by his counsel). The fall of Rochester Castle and Canterbury showed that the rebels were a real threat to the government in London. The King and his council had installed themselves in the Tower of London for their own safety as they knew the rebels approached.

It is estimated the rebels numbered about 60,000 upon arrival in London on. On June 13th, the rebels made it through the gates and proceeded to destroy, loot, pillage, released prisoners, and burn legal/government documents. They began to collect more supporters from the lower classes of London, who had their own personal grievances. The rebels targeted the homes of those on the council. They attacked the manor home of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Simon of Sudbury, and looted and destroyed the home and his belongings. The New Temple, run by the Knights Hospitaller, was targeted to burn the legal documents stored there.

One of their main targets was the Savoy Palace, which was John of Gaunt’s lavish London Palace. It was up in flames by the end of the night. The building’s contents plundered and burned or tossed in the Thames. The Savoy Palace represented the excess and greed of the upper classes due to the opulence of the size and design and the luxury of the furniture. One of the coats belonging to John of Gaunt was hoisted into the air on a pike in victory, then later torn to pieces. Fires and smoke raged on into the night which the occupants of the Tower likely watched with mixture of fear and uncertainty. It was clear that the King was now forced to take action.

On June 14th, the teenaged King Richard left the safety of the Tower and met with the rebels. The King met them in person and asked them to tell him their grievances. The rebels requested freedom for themselves and their descendants. They requested the end of serfdom, the ability to own land and the guarantee that all men were free. They requested a rent limit, which would hold the power of the landlord in check and an end to the unfair poll taxes. The final item was that “no man should be compelled to work except by employment under a regularly reviewed contract (Jones, 115). Richard II agreed to guarantee the rebels these freedoms and would create official charters for each man to reflect this.

Everything seemed to be going well, but the young King would go on to make a grave error. Either due to inexperience or adrenaline, he then stated that the rebels were free to catch those they deemed traitors and bring them before him to be tried by law. The rebels took this as permission to hunt down their enemies and bring about their own justice. That night the rebels invaded the impenetrable Tower of London and met with little resistance. The image of London burning in the background and the rushing mob caused the guards to hesitate. The inhabitants of the Tower (which included many of the King’s council) scrambled to flee due to the fear of what may happen to them. Many were found by the rebels and captured. Simon Sudbury, Archbishop of Canterbury, was pulled from the Chapel while at prayer and brought to Tower Green. He was beheaded by the mob. His head joined others as a trophy which was displayed to London. The rebellion had now fallen into the realm of chaos with many government and tax officials falling victim to these executions.

Richard II had not been in the Tower when the rebels invaded, and he had to have known that his government was in trouble as he watched as the display of heads upon London Bridge increased. A rebellion of this scale from people of the common classes had not happened before. The King had to prepare himself to end this once and for all. He agreed to meet the rebels once again on June 15th at Smithfield. He rode out with 200 retainers and in the company of the Mayor of London, Walworth, who was dressed in armor. The rebels and the royal retinue stood across from each other. Wat Tyler confidently rode out to meet with the royal party. The leader of the rebels, a common man from Essex, was now face to face with the King of England. Tyler gave even more extreme demands, he continued to call for the end of serfdom, but also the end of lordship in its entirety. He called for the abolishment of the Church hierarchy and that all clerical lands should be stripped from the church and divided amongst the people of the parish. Lastly, he demanded that all men should be free and on equal footing.

In response, Richard II essentially told Tyler to go home. The King was done with attempts to negotiate with the rebels and was ready to complete this whole fiasco. Throughout this meeting, Tyler acted arrogantly in front of the King. This included spitting in front of his Royal Highness and then proceeded to mount his horse without the leave. There seems to have been some heckling from the King’s side which triggered Tyler’s anger and he thrusted his dagger at Walworth. The blow glanced off the mayor’s armor and gave Walworth the excuse to plunge his own dagger into Tyler’s neck. Richard II took a risk and rode out to lead the rebels away from the scene before they could understand what had happened, so they would not take revenge before royal forces could regroup. The rebels choose to follow their King.

With their leader dead, the rebellion began to fall apart. Wat Tyler’s head was put on display and became a sign of the end of the rebel cause. Richard II reneged all the promises that he had made. Hundreds of rebels were executed as punishment (including John Ball) and smaller rebellions all around the country were put down. The only victory was that the poll tax was canceled. The Peasants Revolt of 1381 was the coming of age moment for Richard II, and many were impressed by his show of bravery in dealing with the rebels. He begin to take more personal interest in state affairs and would become intolerant to any disobedience to his rule. In 1399, he would be overthrown by Henry Bolingbroke (soon to become King Henry IV), forced to abdicate and imprisoned.

The Peasants Revolt only lasted a few months, but it left a great mark in history. It was one of the most intense rebellions during the medieval era and it was led by the common people. It brought ideals to the forefront regarding freedom, equality, and the rights of all people. It brought attention to class divisions and the greed of the nobility and the church. It showed that the common people did have ideas and opinions about politics and the way their country was run. These ideas would carry on into future rebellions around the world.

Sources:

Jones, Dan. Summer of Blood: England’s First Revolution. New York: Penguin Books, 2016.

https://www.1381.online/about/about_the_revolt

https://www.britannica.com/event/Peasants-Revolt

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/peasant-army-marches-into-london

https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Wat-Tyler-the-Peasants-Revolt

https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Richard-II-king-of-England/Tyranny-and-fall

“The Peasants Revolt 1381” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jjit4oeWjiY&ab_channel=HomeschoolHistory